On reflection, perhaps it shouldn't be surprising. We expect the Chief Scientist to be a genius with a brain the size of a planet who is perpetually on top of their game, but in fact they are a human frequently operating under great stress, and fallible like the rest of us. Nevertheless, his first responsibility - and ours - is to the truth, and it is therefore my task to explain that he unfortunately misled the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee when he appeared before it on Thursday 16th July.

The topic under consideration is SAGE's recommendations around mid-March, when the various restrictions were being introduced - some have argued (and I'm among them) that this happened rather too late, with the result that the country suffered many more deaths, and far greater economic damage, than would have been the case with prompt action.

Most of the interesting action during his appearance was under questioning from Graham Stringer MP, from about 50 minutes in to the video, or

Q1041 on the transcript. Stringer is pressing him on the promtness (or otherwise) of introducing the lockdown, and particularly the speed of response to the data showing more rapid doubling than they had originally assumed:

Q1041 Graham Stringer: As a scientist, I was always taught to forget hypotheses, theories and ideas and look at the data, because having preconceived ideas can distort the way you look at things. When we went into this, scientists in this country were looking at data from China that showed a doubling of the infection every six or seven days. When you looked at our data closely, the infection death rates were doubling every 30 to 36 hours. Why didn’t you and SAGE advise the Government to change their attitude because, if you had looked at that and given that advice, the lockdown might have happened earlier?

To start with, to avoid the usual tedious ducking and weaving from the usual tedious suspects, it's important to be clear about the terms. When Stringer and Vallance are talking about “lockdown”, they mean the strict policies from the 23rd March onwards, when we were told to stay at home, all non-essential shopping and travel was forbidden, etc. As Vallance puts it:

there was a series of steps in the run-up to lockdown, which started with the isolation of people who had come from China, but the main ones were: case isolation; household isolation; and recommendations not to go to pubs, theatres and so on.

So, “lockdown” here means policies of the 23rd March, as also confirmed by

Hancock in Hansard:

the level of daily deaths is lower than at any time since lockdown began on 23 March.

Sorry for this tedious pedantry, but experience has shown some people will, having lost the argument about timing, duck and weave about what "lockdown" means in the first place.

So, back to the timing. Vallance's main claim, which I will argue is incorrect, is contained in the following sentences:

When the SAGE sub-group on modelling, SPI-M, saw that the doubling time had gone down to three days, which was in the middle of March, that was when the advice SAGE issued was that the remainder of the measures should be introduced as soon as possible. I think that advice was given on 16 or 18 March, and that was when those data became available.

Note how clear he is that this advice to introduce the remainder of the measures - ie implementation of the full lockdown - was based on the realisation that the doubling time was as short as 3 days. I'll let him off with his use of “had gone down to” - in reality the doubling time had not changed at all, it was just SAGE's realisation that had gone down, but I will be generous and attribute this to sloppy language. He emphasises this reliance on the new data repeatedly:

Sir Patrick Vallance: Knowledge of the three-day doubling rate became evident during the week before.

Q1042 Graham Stringer: Did it immediately affect the recommendations on what to do?

Sir Patrick Vallance: It absolutely affected the recommendations on what to do, which was that the remaining measures should be implemented as soon as possible. I think that was the advice given.

and again:

Sir Patrick Vallance: The advice changed because the doubling rate of the epidemic was seen to be down to three days instead of six or seven days. We did not explicitly say how many weeks we were behind Italy as a reason to change; it was the doubling time, and the realisation that, on the basis of the data, we were further ahead in the epidemic than had been thought by the modelling groups up until that time.

So he is absolutely certain that the advice to proceed full steam ahead on the lockdown was predicated on the new 3 day doubling time.

However, he also claimed that this advice was given “on 16 or 18 March.” This is the critical error in his statements, that prompted this blog. Some people have jumped on this claim (and to be fair to Vallance, he was obviously unsure of the exact date in his response) to argue that the Govt was slow to react to SAGE's recommendation, and that this was the cause of the late lockdown and large death toll.

Unfortunately, Vallance was mistaken with his dates. In fact, SAGE actually still thought the doubling time was 5-6 days on the 16th March (

minutes):

UK cases may be doubling in number every 5-6 days.

and by the 18th March their estimate was even slightly longer (

minutes):

Assuming a doubling time of around 5-7 days continues to be reasonable.

It is therefore not at all surprising that the minutes of these two meetings do not contain any recommendation, or even a hint of a suggestion of a recommendation, that we should proceed with haste to a full lockdown. In fact the minutes of the 18th March make the very specific and detailed recommendation that schools should be shut, with the clear statement that further action would only be necessary “if compliance rates are low” (NB compliance with all measures has been consistently higher than in the modelling assumptions):

2. SAGE advises that available evidence now supports implementing school closures on a national level as soon as practicable to prevent NHS intensive care capacity being exceeded.

3. SAGE advises that the measures already announced should have a significant effect, provided compliance rates are good and in line with the assumptions. Additional measures will be needed if compliance rates are low.

Incidentally, this is why we have to be precise about what “lockdown” means, so that certain people don't pivot to “Aha! They said we should shut something! Vallance was right all along!” SAGE here is not recommending “lockdown” in the sense used by Vallance, Stringer, Hancock, or anyone else. They are only recommending school closures, which the Govt did implement promptly at that time.

Now let's go back to this from Vallance:

When the SAGE sub-group on modelling, SPI-M, saw that the doubling time had gone down to three days, which was in the middle of March, that was when the advice SAGE issued was that the remainder of the measures should be introduced as soon as possible.

The relevant SPI-M meeting at which they reduced their estimate of doubling time was actually on the 20th March (

minutes). At this meeting, they abruptly realised:

Nowcasting and forecasting of the current situation in the UK suggests that the doubling time of cases accruing in ICU is short, ranging from 3 to 5 days.

[...]

The observed rapid increase in ICU admissions is consistent with a higher reproduction number than 2.4 previously estimated and modelled; we cannot rule out it being higher than 3.

All well and good, but a week late.

The nest SAGE meeting was on the 23rd (21st-22nd was a weekend) and at this point they conclude (

minutes):

The accumulation of cases over the previous two weeks suggests the reproduction number is slightly higher than previously reported. The science suggests this is now around 2.6-2.8. The doubling time for ICU patients is estimated to be 3-4 days.

(NB doubling time is in principle the same for all measures of the outbreak, ignoring transient effects as the epidemic gets established. That's why it is such a useful concept and measure.)

SAGE also state at this meeting on the 23rd:

Case numbers in London could exceed NHS capacity within the next 10 days on the current trajectory.

They don't explicitly minute the need for a tight lockdown, but certainly provide statements that point in that direction, such as:

High rates of compliance for social distancing will be needed to bring the reproduction number below one and to bring cases within NHS capacity.

It seems reasonable to conclude that the message taken from this meeting was that London at least was on the verge of exceeding capacity and that strong measures needed to be urgently taken to slow transmission. As Vallance had put it:

the remaining measures should be implemented as soon as possible.

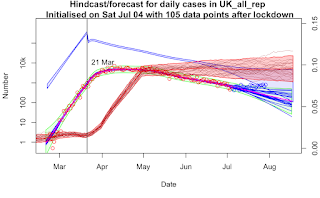

So it seems that Vallance has described the narrative arc precisely as the minutes of all the meetings around this time describe, but for the important fact that he got the date of this final recommendation wrong. He appears to have created a false memory of a world where the heroes of SAGE worked it all out in the nick of time, and told the government....who then sat on this information and delayed lockdown for a week. It's a nice story, but it's not actually what happened. The data were certainly clear to many by mid-March (ie the 14th, prior to the famously uncalibrated runs of the Imperial College model) but SAGE resolutely ignored and rejected this evidence for a further week, and this delay caused huge unnecessary harm to the country.

This would be a minor tale of a small slip of memory, were it not for the unfortunate fact that various factions have glommed onto Vallance's statement as proof that the scientists were blameless and the Govt guilty. Most egregiously, SAGE member Jeremy Farrar tweeted:

To make the mistake that Vallance did, under pressure of live questioning, is forgivable. To double down on the error from the comfort of your own computer, when the documentation is freely available, is not. The minutes prove that SAGE did not accept the evidence of the short doubling time on the 16th and 18th March. It is quite possible that some SAGE members - perhaps including Farrar - had tried to sound the alarm about the rapid doubling at an earlier time. However, they did not carry the day and I find no evidence that they spoke up in public either. SAGE did not recommend lockdown prior to the 23rd March, however much it suits various peoples' agendas to claim so.